Cardinal

Wolsey's college in Ipswich

The Thomas Wolsey public house, Who was Thomas Wolsey?

A major strand in the history of the town concerns its most famous

(some might say notorious) son, Thomas Wolsey (c.1475-1530). There are

a few features

within today's Ipswich to remind us of the man who was to rise to

become the second most powerful man in the kingdom of the mercurial

Henry VIII.

The plaque on Curson

Lodge in St Nicholas Street reminds us of his origins. Wolsey's

Gate, albeit worn away by pollution, weather and time, still stands in

College Street, close to the docks. This watergate to the college is

the only physical remnant of Wolsey's great scheme to establish a

school linked to his own Cardinal College in Oxford; a school to rival

Eton or Winchester. However, there are one or two clues in the street

names of Ipswich.

Turret House

1778 map

1778 map

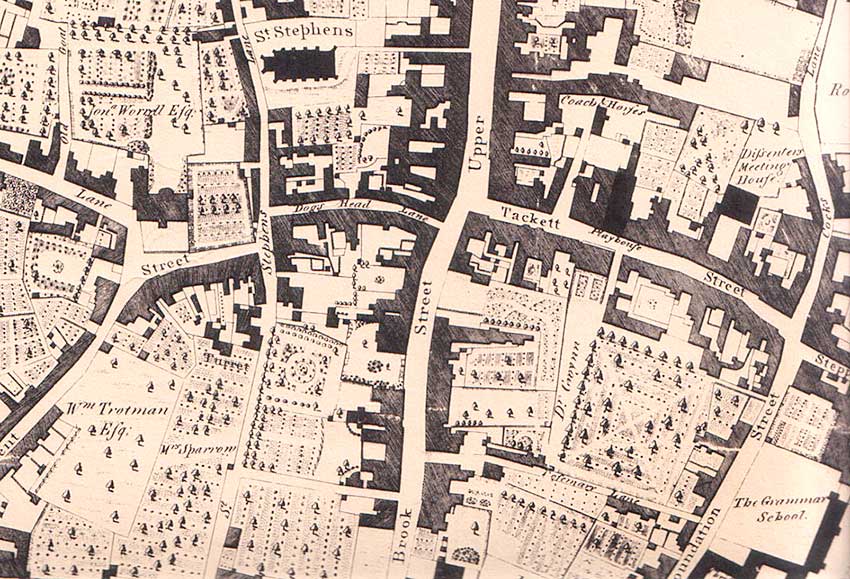

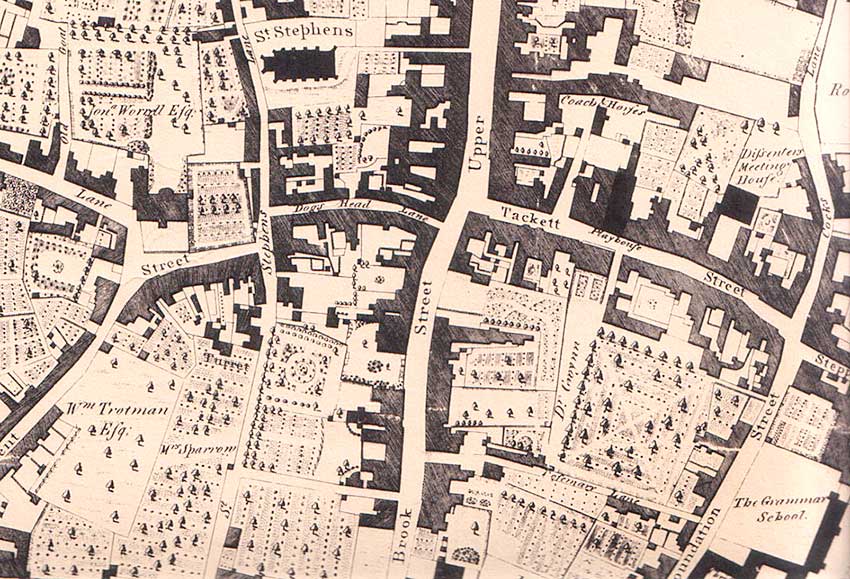

The map detail above from Pennington's map of

Ipswich 1778 clearly labels a house at lower centre-left: 'Turret'.

The north-south street, which today we know as Turret Lane, is here

labelled St Stephens Lane and was one of the ancient ways from the dock

to the heart of the town.

Turret Lane is named

after the Turret

(Garden) House which was demolished in 1843. It is a later name for

what must have been the

Dean's House to the north of the college site and which formed the main

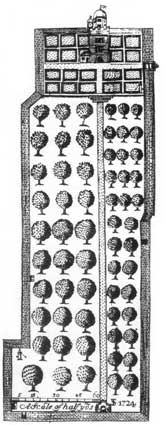

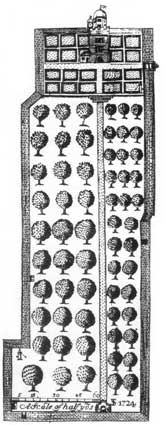

entrance to Wolsey's College. The plan illustrated here, dated 1724,

shows the house at the top,

with turrets echoing those which are decribed as adorning the college

buildings. The positioning of this house and its gardens is indicated

on the sketch map of the whole college site as it was in 1528. The

red outline shape fits onto the upper part of Ogilby's

1674 map almost exactly

(down as far as Rose Lane).

Turret Lane is named

after the Turret

(Garden) House which was demolished in 1843. It is a later name for

what must have been the

Dean's House to the north of the college site and which formed the main

entrance to Wolsey's College. The plan illustrated here, dated 1724,

shows the house at the top,

with turrets echoing those which are decribed as adorning the college

buildings. The positioning of this house and its gardens is indicated

on the sketch map of the whole college site as it was in 1528. The

red outline shape fits onto the upper part of Ogilby's

1674 map almost exactly

(down as far as Rose Lane).

1674

map

1674

map

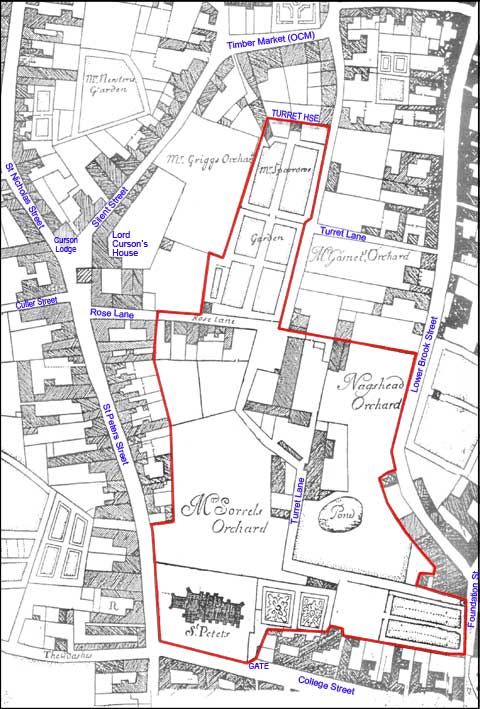

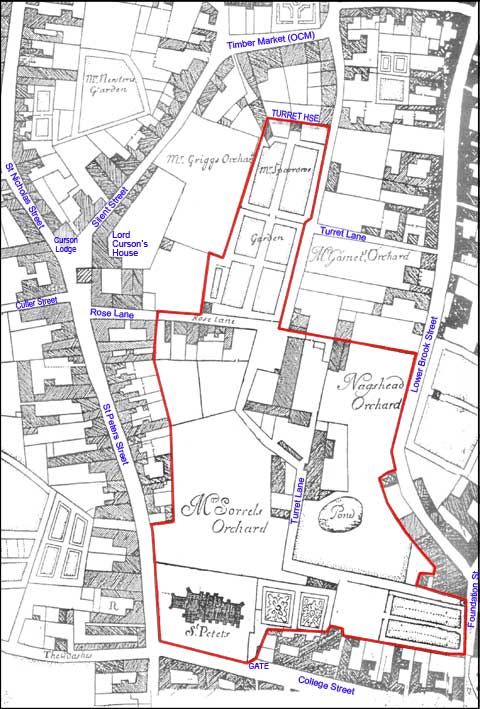

Notes on the map of Wolsey's College

1. The red outline indicates

the probable extent of Wolsey's College with

the area later known as 'Mr Sparrow's Garden' (with Turret House at the

top) to the north of the site. More recent street names are indicated

in blue.

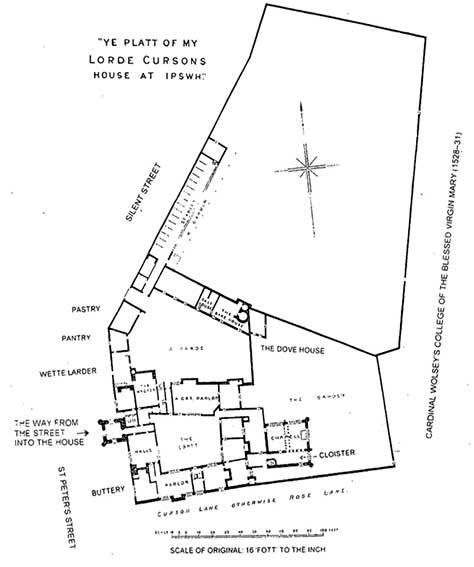

2. Lord Curson's House at the

upper left of the site is shown in more detail below. Wolsey intended

to requisition this property as his own retirement home, adjoining

his much-vaunted College. Curson could hardly refuse but, having

asked for three years grace, he kept his head down and was saved by the

fall of Wolsey, the College was lost and so he retained his home.

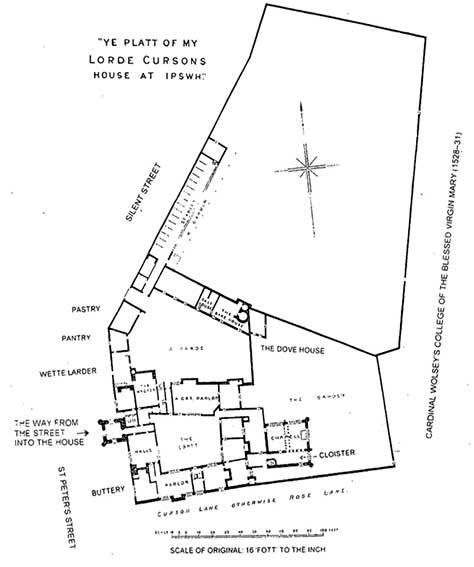

Above: a traced copy of the Tudor plan of Curson House (with extra

captions in larger font from those on the original) taken from Sir

Robert, Lord Curson, soldier, courtier and spy, and his Ipswich mansion by John Blatchly and Bill Haward,

Ipswich Institute of Archaeology and History research paper.

3. Rose

Lane is shown as the southern limit of Lord Curson's House, here

labelled 'Curson Lane otherwise Rose Lane').

3. Foundation

Street was home

to an early incarnation of Ipswich Grammar School ('The Ipswich

School'). Merchant and

politician, Richard Felaw, left his

house in the street (then called St Edmund Pountney Lane) as a home

for

the school, endowing it with the income from lands at Whitton so that

children of needy parents

could attend without paying fees. One of the earliest beneficiaries was

a young Thomas Wolsey, later Cardinal Archbishop of York and Lord

Chancellor of England. See also our Lower

Brook Street page for more about Rosemary Lane and St Edmund de

Pountenay chapel.

4. Wolsey's likeness is

'celebrated' on a plaque on the side entrance to

the Wolsey Gallery (and Wolsey Garden) behind Christchurch Mansion.

5. Lady Lane is the remainder of the site of

Gracechurch, the shrine of Ipswich (as documented by Lord Curson

himself). Wolsey intended to capitalise on

the fame and success of the shrine by linking it to his College.

6. Cardinal Street, New Cardinal

Street and

Wolsey Street near Greyfriars are obvious nods to the man, as are

Wolsey Court, Wolsey Gardens and Cardinal's Court.

2020 image

2020 image

Above: this larger than life-size bust of Wolsey sits upstairs in the

Town Hall; the sculpture was made specifically for that building by

local sculptor James Williams in 1871. We have recently

heard about another likeness by Robert Mellamphy in plaster-of-paris

which resided for around twenty years in St Peter on the Waterfront and

was moved to the vestry of St

Clement Church and may, we had hoped, be made into a 'proper' bronze.

However, an opening of St Clement in May 2014 reveals that it has quite

a high level of dampness in the air and we hear from Dr John Blatchly

that the maquette in

chicken wire and plaster had begun to collapse. Apparently Robert

Mellamphy's family have returned it to his studio, but it is perhaps

unlikely that it will be cast. We wonder if anyone ever photographed

it? These

likenesses are joined by the somewhat controversial, 21st century Wolsey

statue in St Peter's Street, outside the site of Curson House.

There is a public house called, since September 2011, The Thomas Wolsey

in St

Peters Street (see below).

Cardinal Wolsey (1610) by Sampson

Strong with Christ Church in the background; the

painting is kept at

Christ Church College, Oxford.

Although it would be difficult to find a better example of abuses in

the Church than the Cardinal himself, Wolsey appeared to make some

steps towards reform. In 1524 and 1527 he used his powers as papal

legate to dissolve thirty decayed monasteries where corruption had run

rife, including abbeys in Ipswich and Oxford. However, he then used the

income to found a grammar school in Ipswich (The King's School,

Ipswich, later Ipswich School) and Cardinal College in Oxford. The

college in Oxford was renamed King's College after Wolsey's fall.

Today, it is known as Christ Church. Wolsey died five years before

Henry's dissolution of the monasteries en masse began.

A chronology of Wolsey's college

(based on Dr John Blatchly’s excellent book A famous antient seed-plot of learning,

see Reading list)

1526

6 May. Papal bull for the

establishment of the Ipswich College sent from Rome to Wolsey by Bishop

Worcester, auditor of your Apostolic Chamber there.

1527

November. Thomas Cromwell,

friend and follower of Wolsey,

visits Ipswich about the building of the college.

1528

March. The Duke of Norfolk

writes to tell Wolsey that he has visited the site and ordered a plan

of St Peter and St Paul Priory. He can advise the Cardinal how to ‘save

large monie in buildyng there’, presumably by using some of the priory

buildings, particularly by modifying the Church of St Peter as the

chapel.

14 May. Pope Clement VII

issues a bull authorising the suppression of five small priories

including Felixstowe and Blythburgh (the latter the subject of a Time

Team programme on Channel 4, which can be viewed on the web).

26 May. King Henry VIII

ratifies a bull for the suppression of the Augustinian priory of St

Peter and St Paul in Ipswich

31 May. The king ratifies the

bull for the transfer from Wolsey’s Oxford College of five priories

including Snape and Dodnash.

15 June. The foundation stone

of the college is laid by John Holte, titular bishop of Lydda and a

suffragan of London. In the 18th century the stone was found built into

wall in Friars Road (which ran between Friars Street and Wolsey Street:

it no longer exists) and was presented to Christ Church, Oxford by the

Rev. Richard Canning, where it is kept in the chapter

house.

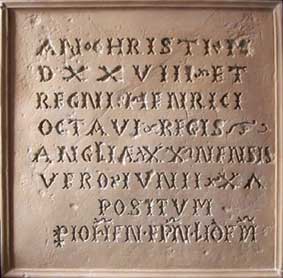

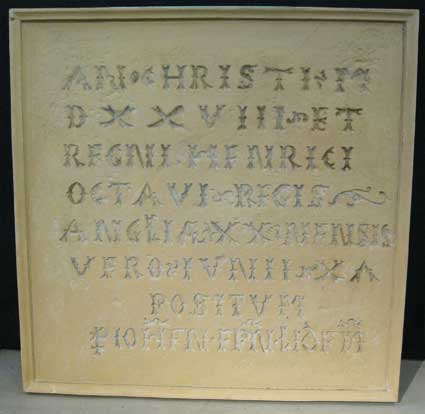

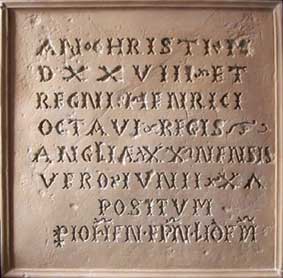

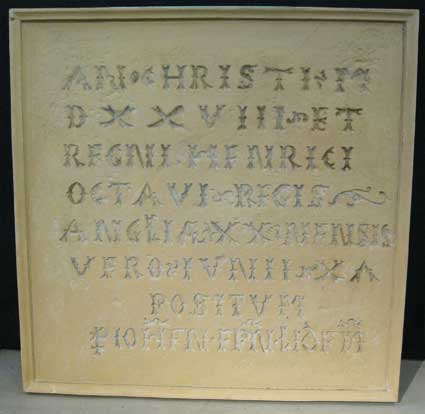

Wolsey's

College foundation stone

Wolsey's

College foundation stone  Facsimile in St Peter's

Facsimile in St Peter's

'AN . CHRISTI . M

DXXVIII . ET

REGNI . HENRICI

OCTAVI . REGIS

ANGLIĘ XX . MENSIS

VERO . IUNII . XV

POSITUM

p . IOHEM . EPN . LIDEM'

The translation is: 'This year of our Lord 1528 and the 20th

year of

the Reign of King Henry VIII of England and the 15th of June [this

stone] laid by John [Holt], Bishop of Lydda'.

21 June. Building work is

begun by thirty-seven freemasons working under local master masons,

John Barbour and Richard Lee, using Caen stone. Mr Daundy, Wolsey’s

cousin, has imported a 121 tons and promises 1,000 more before the

following Easter.

26 June. The king grants the

rectory of St Matthew’s, Ipswich to the college, a living held at the

time by Wolsey’s natural son, Thomas Winter.

29 June. The King's letters

patent for the foundation of the college are issued. It could be built

in St Matthew’s parish (‘where the said Cardinal was born’) or

elsewhere.

30 June. Cromwell to Thomas

Arundel: he must delay erection of the college at Ipswich until 21

July as the offices of Chancery will not expire till then.

3 July. Wolsey commissions six

eminent clerics including Stephen Gardiner, later Bishop of Winchester,

to prepare statutes for the college.

28 July. Wolsey executes his

foundation deed, based on the king’s letters patent, converting St

Peter and St Paul Priory to ‘Saint Mary, Cardynall College of Ipswich’.

William Capon STP, master of Jesus College, Cambridge is appointed dean

of the college, presiding over twelve priest fellows, eight clerks,

eight children (choristers), a grammar-school master and usher, fifty

grammar scholars and ’12 poure men to pray dayly to God for the good

astate of our Graces King & the said Cardinall, ther friends souls

and all christen soulls’. Later Thomas Cromwell makes draft lists of

stipends (the dean and master both have £13 6 shillings and eightpence)

and adds a second usher, who is ‘keeper of the scholehouse’.

7 August. Wolsey, from his

mansion Hampton Court, instructs Dean Capon to assemble the

parishioners of St Peter's and offer them the choice of St Nicholas or

St Mary-At-The-Quay for their future

worship. In her will, Dame

Elizabeth Gelget leaves money for the purchase of a roof from Capon

should the churchwardens of St Mary-At-The-Quay choose to cover the

chancel there with it. The congregation there, about to be swelled by

about half the parishioners of St Peter’s, would need a church in good

order. St Mary-At-The-Quay chancel roof shows every sign of being

roughly reassembled probably from St Peter’s.

Wolsey wanted his chapel to resemble those of Eton and King’s: squarer

than the traditional long cruciform shape and better for grand

ceremonial. The Tournai marble font basin, lacking its large central

pillar and four slender ones at the corners, is given an incongruous

Tudor base. The west doorway of St Peter's was embellished with heads,

shields and fleurons (flower shaped ornaments) in the jambs and two

large vaulted canopied niches to north and south, probably for statues

of St Peter and St Paul. This is Tudor rather than medieval work.

10 August. Dean Capon

publishes the acquisition of many smaller properties given by Wolsey

with the king's approval. The deed is dated from ‘the chapel of our

said college’, that is, the refurbished St Peter’s.

20 August. The king inspects

and confirms a papal bull dated 12 June exempting the college from all

ecclesiastical jurisdiction but that of the pope, that two archbishops

being guardians of its liberties.

1 September. The college in

session under William Goldwin, master. Wolsey sends his Rudimenta

Grammatices, ‘dedicated not only to Ipswich School, most happily

founded by the most reverend Lord Thomas, Cardinal of York, back to all

other schools in England’.

8 September. Feast of the

nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary. Capon writes at length describing

to Wolsey – who could not be present – the first annual

celebration of the foundation. After solemn mass the planned procession

to Gracechurch in Lady Lane is interrupted by rain, but a lavish feast

is enjoyed nevertheless.

See our Wolsey

450 page for a contemporary map of the procession route.

Wednesday after Christmas. The

Great Court grants the colour college the interest in all the property,

in Ipswich and at Whitton, with which Richard Felaw endowed the grammar

school. Against ‘Concessio’ [granted] in the margin is written ‘Vacat'

[void], showing that the corporation managed to reverse the grant after

the fall of the college.

1529

10 January. William Goldwin

writes to Wolsey reporting progress and, presumably by the same

messenger, the bailiffs reply to Wolsey’s request that they grant the

college the former endowments of the grammar school.

12 April. Capon writes to

Cromwell: they have begun to set the freestone; there are troubles with

the choir. But the school is so well attended that it must be enlarged;

schoolmaster and usher take great pains.

30 April. Sir Robert Curson

(Lord Curson) agrees to Wolsey’s request that he, Curson, give his own

house on St Peters Street, adjoining the college, as his ‘provost’s

residence’ in the manner of the provosts of Eton and Winchester. Robert

Curson cannily asks for three year’s grace to move out thus avoiding

the need ever to do so, due the imminent fall of both Wolsey and his

college at Ipswich.

July. Thomas Cromwell’s agent

Brabazon reports that the college is going on prosperously ‘and much of

it above ground, which is very curious work’. Working day and night,

more has been done in the last three weeks then for some time before.

July to September. Gifts,

plate,

investments, books and other furnishings for the chapel arrived from

many sources including Wolsey’s York Place in London [see below].

8 August. Bailiffs and portman

write to thank Wolsey for setting up the college to the honour and use

of the town.

8 September. It is not known

whether the second Lady Day procession was held.

13 November. Royal

commissioners visit to make an inventory of all valuables and building

materials. They estimate that the college had £10,000 worth of Wolsey’s

‘treasure’ and take away with them the best plate and vestments.

1 December. Wolsey is

impeached.

1530

9 July and 20 July. Dean Capon

writes twice to Wolsey, in his first expressing pessimism about the

future, the second telling him that the king was resolved to dissolve

the college by Michaelmas.

19 September. Commissioners

sitting at Woodbridge rule that all the college lands are forfeit to

the king.

4 October. Capon tells Wolsey

that the Duke of Norfolk has ordered the dissolution of the college,

retaining only the dean, sub-dean, schoolmaster, usher and six grammar

children pending the king’s pleasure. The king orders the demolition of

the college and the materials to be shipped to Galye Quay in London

where they are to be used to enlarge what was formerly Wolsey’s York

Place to become the royal palace of Whitehall. Only Wolsey’s Gate, the

waterside entrance to the Ipswich college next to the (St Peter)

chapel, remains today on the suitably named College Street.

2014 images

2014 images

From the Cornhill and the Buttermarket visitors passed under an

impressive tower and walked through a long formal garden. The Turret

House [see the top of this page], as it was latterly called, was pulled

down in 1843. It was

probably a remnant of the Dean's house, well situated, at some remove

from the boys, for entertaining guests.

29 November. Wolsey dies at

Leicester Abbey on his way to London.

Wolsey’s remains were interred somewhere within the abbey’s church,

possibly in the Lady Chapel, where they are thought to remain; however

the exact location of his burial is unknown. A more recent memorial

slab can be found in Abbey Park, Leicester, all that remains of the

Augustinian Abbey of St Mary de Pratis which was 'dissolved' in 1538.

The slab bears Wolsey's coat of arms.

Early 1531

Ipswich college property bringing in an income of £2,234 a year

was assigned to the Oxford college (now to be known as King's College

of

Christ Church), St George’s Windsor, the king and various other

persons. Thomas Alvard (stepson of Sir

Thomas Rush), agent of Thomas Cromwell, is given the college

site.

Rush and Alvard were canny political survivors and they

certainly had an eye to business. When the fallen Wolsey’s college was

closed down and the fabric dismantled and stockpiled on the site, it

was appropriated by the king. Rush and Alvard won the contract to

transport most of it to Westminster (to be used on the building of

Whitehall Palace?) and no doubt made a decent percentage on the value.

Some idea of the scale of the college campus can be guaged from the

fact that the Exchequer accounts of 1531 record 1,300 tons of Caen

stone (initially imported from Normandy – Ipswich doesn’t have local

supplies of stone) and 600 tons of flints (initially brought to Ipswich

from the cliffs in Harwich).

(For more about Rush and Alvard see our Old

Cattle Market page under 'Sir Thomas Rush and the Church of St

Stephen'.)

Most importantly, the ‘college or school’ of Ipswich was

assigned

£60 a year – in another document only £43 – to cover the stipends of

master and usher and to be paid out of the profits of crown lands in

the county, but Felaw’s bequests were not mentioned as probably already

recovered by the corporation. Thomas Cromwell is still credited with

ensuring that the school was not forgotten in the dissolution of the

short-lived college.

See also our Christ's Hospital

School page for more on the story of The Grammar School, today

Ipswich School.

York Place / White Hall

By the 13th century, the Palace of Westminster had become the

centre of government in England, and had been the main London residence

of the king since 1049. The surrounding area became a very popular and

expensive location. The archbishop of York, Walter de Grey, bought a

property in the area as his London residence soon after 1240, calling

it York Place.

Edward I of England stayed at the property on several occasions while

work was carried out at Westminster, and enlarged the building to

accommodate his entourage. York Place was rebuilt during the

15th century and expanded so much by Cardinal Wolsey that it was

rivalled by only Lambeth Palace as the greatest house in London – the

king's London palaces included. Consequently, when King Henry VIII

removed the Wolsey from power in 1530, he acquired York Place to

replace Westminster as his main London residence. He inspected its

treasures in the company of Anne Boleyn. The phrase Whitehall or White

Hall is first recorded in 1532; it had its origins in the white stone

used for the buildings.

The Palace of Whitehall (or Palace of White Hall) was the main

residence of the English monarchs in London from 1530 until 1698 when

all except Inigo Jones's 1622 Banqueting House was destroyed by fire.

Before the fire it had grown to be the largest palace in Europe, with

over 1,500 rooms, overtaking the Vatican and Versailles. The

palace gives its name, Whitehall, to the road on which many of the

current administrative buildings of the United Kingdom government

are situated, and hence to the central government itself.

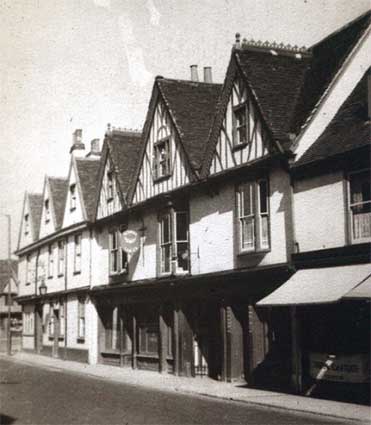

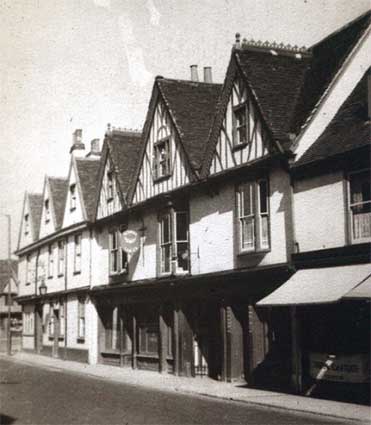

The Thomas Wolsey public house,

9 St Peters St

1960s

image courtesy The Ipswich Society Image Archive

1960s

image courtesy The Ipswich Society Image Archive

Today's Thomas Wolsey public house with timbering in the three gables;

the Rose Inn/Rose Hotel comprises the three gables to the left.

Now that we have this web page in place we, at last, have a place to

show Tudor mouldings from an interior ceiling in the Thomas Wolsey

public house in St Peters Street, once a fine merchant's house and yard.

It stands next door

to the Rose Hotel with its vestigial 'Cobbolds'

lettering. Interestingly, Chris Sedlak states

that: 'The former

inn is on the corner, as you know, and to its south is a slightly older

building (late 1500s / very early 1600s vs. early-to-mid 1600s for the

inn structure), the Rose House,

which was a succession of pubs in the

20th and now 21st centuries... My guess is that the Rose Inn (namesake

of the lane) was named after the slightly older and adjacent Rose

House.' [Update taken from our page on the Rose Hotel.]

This building is Listed Grade II and

dates from the 17th century. It was converted

into a large single ground floor bar with upstairs rooms and a narrow

staircase leading to the Tudor parlour. It was renamed The Thomas

Wolsey public house in September 2011. There is a

seated drinking

area in the courtyard and beneath the carriage entrance, which has one

of the public rooms above.

The Thomas Wolsey was previously called Rapps in early 1980s,

The Black Adder in the early 1990s when ex-footballer Alan Brazil

owned the pub for several years. A friend of this website, Linda Wilde,

made the excellent snakish engraved glass sheets which hung in the

front windows of the Black Adder – we wonder where they ended up?

Before it was called The Thomas Wolsey it was called 'bar IV'.

Flying pigs are a favoured motif, emblem of the Bacon family who

once lived here. Pink Floyd and Gerald Scarfe were obviously taking

note [contemprary cultural reference from the 1970s...] Also Tudor

roses,

grotesque horned men (perhaps green men, as seen on the Tolly Cobbold brewery?) and other animals.

The room also has a fine fireplace with carved wood overmantle.

The Listing text is shown below (British Listed buildings, see Links):-

"A C17 timber-framed and plastered house, similar in design to Nos 3

and 5, with 3 jettied gables on paired brackets. Altered in the C19.

The gables have C19 cut and shaped ornamental bargeboards and sham

exposed timber-framing. 3 window range, early C19 bay windows on the

1st storey, double-hung sashes with vertical glazing bars. The attics

are lit by windows in the gables. The ground storey has C19 shop

windows and a carriage way to a small courtyard at the rear. A

continuous fascia with an unusual modillion cornice unites the ground

storey. At the rear 2 wings extend to the east. On the north side there

is a 2 storey wing with a range of casement windows with lattice leaded

lights and a single storey extension at the east end. On the south side

there is a jettied upper storey with exposed joists and a range of

casement windows similar to those on the south side. The ground storey

has brick nogging and a boarded door with a Tudor arched head. The

window above the carriage entrance is an oriel bay with leaded lattice

lights and a moulded sill. The wings at the rear have been restored.

Roofs tiled.

Nos 5 to 13 (odd), No 13A, Nos 15 to 33 (odd), No 33A and Nos 35 to 39

(odd) form a group."

Wolsey... who he?

2022 marks 550 years (ish) since the birth of the most famous

son of Ipswich. Thomas Wolsey (c.1472-5 to 1530 – his date of birth is

uncertain). His birthplace was probably a house

in St Nicholas Street (or St Nicholas Church Lane), long since

demolished, at the corner of a passage into the churchyard; another

candidate is the site of today's Black

Horse public house in Black

Horse Lane. Uncertainties about the details of Wolsey's

life are an odd feature of one of the most powerful men in English

history. He became a priest and statesman from relatively humble

beginnings in Ipswich§,

who was blessed with academic brilliance, rapacious ambition and, until

the end of his life, good fortune. It’s a

matter of opinion which of Wolsey's characteristics was more

responsible for his rise to become first minister of Henry VIII, and

chief political confidant, but once he had got to the top, he had a lot

to offer.

He was perhaps the finest ministerial mind England had ever had until

at least the 19th century. He was obsessional in his micro-management

of affairs of state and refusal to delegate – his overwork was to take

its toll on his health over a long period. In many ways, Wolsey led a

charmed life. The young Wolsey benefitted greatly from the patronage of

the rich and powerful who recognised his gifts and potential. He

secured the scholarship to Ipswich Grammar School, a bequest of Tudor

merchant, Richard Felaw, later studying

theology at Magdalen College,

Oxford – his education promoted by his uncle, Edmund Daundy. As his

power increased he collected ecclesiastical titles and properties like

stamps and enjoyed the finest luxuries. His greed accounts for his

later corpulence and poor health.

He went from being a royal chaplain to the Bishop of Lincoln, then

became Archbishop of York and finally Lord Chancellor of England. He

also became Cardinal Wolsey, Papal Legate whose authority from the Pope

in some respects went beyond that of King Henry VIII himself. Wolsey

began building Hampton Court Palace in 1514, and carried on making

improvements throughout the 1520s. Descriptions record rich

tapestry-lined apartments; a visitor had to traverse eight rooms before

finding his audience chamber. He always embraced the trappings and

rituals which people expected of a man of power, they also satisfied

his vanity.

His passion for education influenced his foundation of and endowments

to ‘Cardinal’s College’, today’s Christ Church College in Oxford. He

then turned his attention and wealth to the establishment of a college

dedicated to St Mary The Virgin in his home town to act as a feeder

college to Oxford. He seized the Church

of St Peter to be used as the

college chapel, which was eventually only returned to the parish

through the good offices of Wolsey’s right-hand man and successor,

Thomas Cromwell. The College was almost completed to high standards of

building and materials, but within two years was forfeit to the King,

as was Hampton Court and all of Wolsey’s estate. The only trace we have

of

the College is the much-eroded Wolsey’s Gate, the Watergate,

still to be seen on today’s College Street where the quayside would

have been.

Cardinal Wolsey was accused, after his death, of imagining himself the

equal of sovereigns, and his fall from power was seen as a natural

consequence of arrogance and overarching ambition. Much of this can be

seen as black propaganda spread by his enemies, now that Wolsey was out

of the way of their own ambitions. Yet Wolsey was also a diligent

statesman, who worked hard to translate Henry VIII’s own dreams and

mercurial ambitions into effective domestic and foreign policy. When he

failed to do so, most notably when Henry’s plans to divorce Katherine

of Aragon were thwarted by Katherine herself and the Pope, his fall

from favour was swift and final. Thomas Wolsey died on his way to a

possible last and fatal meeting with royal wrath, at Leicester Abbey in

1530.

Over the fourteen years of his chancellorship, Cardinal Wolsey had more

power than any other Crown servant in English history. As long as he

was in the king’s favour, Wolsey had a large amount of freedom within

the domestic sphere, and had his hand in nearly every aspect of its

ruling. For much of the time, Henry VIII had complete confidence in him

and, as Henry's interests inclined more towards foreign policy, he was

willing to give Wolsey a free hand in reforming the management of

domestic affairs, for which Wolsey had grand plans in the fields of

taxation, justice and church reforms.

The man who was a unique cocktail of merits and failings – perhaps this

lay at the very heart of his extraordinary success. Was he likeable?

Would we have admired or feared him? How is he remembered today? I

recently read an excellent biography of the man – and there are a

number of such books available – John Matusiak’s Wolsey: the life of

King Henry VIII's cardinal (see Reading

list) which reads like a novel and is most enlightening. Copies are

available from Suffolk Libraries. Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall, later

dramatised for television shows us a Wolsey towards the end of his

power (and life). The only known painting of Wolsey by Sampson Strong

was made at least sixty years after his death – it may have been a copy

of a contemporary portrait. It now hangs in Christ Church College,

Oxford. All

subsequent images of the cardinal are based on this unflattering

profile. We don’t really know what he looked like; in fact, he called

himself ‘Wulcy’... An enigma.

[§His

father was either a dodgy Ipswich butcher or ‘a prosperous Ipswich

merchant’– or something in between.]

Above: one of the Ipswich street nameplates which commemorate

the Cardinal (see Street name derivations).

See the Historical

Portraits Picture Archive for an excellent short biography of the

Thomas Wolsey. Also the statue of Wolsey

on Curson Plain.

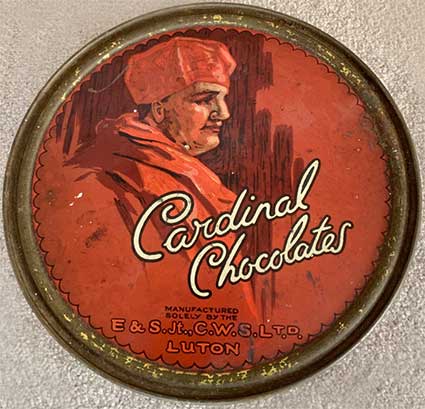

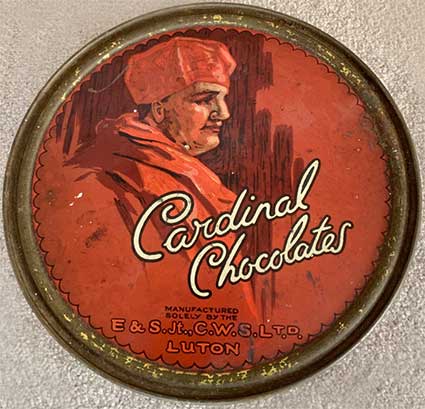

[UPDATE 21.4.2021: And just to prove that the shadow of

Thomas Wolsey is long enough to reach twentieth century marketing,

Syvia Patsalides writes: 'I read the article about the

Silburys, lockdown and Cardinal Wolsey [Ipswich Society Newsletter: Issue

225] and attach a

photograph of my Wolsey Chocolates tin produced by E & S CWS Ltd of

Luton. I believe that the factory in Luton used to do all the chocolate

related stuff, but will admit to have so far done little research. What

chocolates were contained within I wonder?']

2021

image courtesy Syvia Patsalides

2021

image courtesy Syvia Patsalides

'Cardinal

Chocolates

MANUFACTURED

BY THE

E & S. Jt.,C.W.S.LT.D.

LUTON'

Reading: Matusiak, John: Wolsey : the life of King Henry VIII's

cardinal (see Reading list).

See also our Old Cattle Market

page for Wolsey's friend and contemporary at Court, Sir Thomas Rush,

his mansion in Upper Brook Street and his memorial chapel in St Stephen

Church.

For more on the ancient charity schools of Ipswich, see our Christ's Hospital School page.

Related pages:

Wolsey Pageant 1930

Wolsey 450

Wolsey550

Wolsey statue

Christchurch Park &

Mansion (under The Wolsey Art

Gallery/Wolsey Garden)

The Question Mark

Christie's

warehouse

Bridge

Street

Burton Son & Sanders / Paul's

College Street

Coprolite

Street

Cranfield's

Flour Mill

Custom House

Trinity

House buoy

Edward

Fison Ltd

Ground-level dockside furniture

on: 'The

island', the northern quays

and Ransome's

Orwell Works

Ipswich

Whaling Station?

Isaac Lord

Neptune Inn

clock, garden

and interior

Isaac

Lord 2

The Island

John Good and Sons

Merchant

seamen's memorial

The Mill

Nova Scotia

House

New Cut East

Quay

nameplates

R&W Paul malting

company

Ransomes

Steam

Packet Hotel

Stoke

Bridge(s)

Waterfront

Regeneration Scheme

A chance to

compare

Wet Dock 1970s with 2004

Wet Dock maps

Davy's

illustration of the laying of the Wet Dock lock foundation stone,

1839

Outside

the Wet Dock

Maritime Ipswich

'82 festival

See also:

Grand Ipswich

timeline for two thousand years of the town's history;

Ipswich invasions timeline to

see all the raiders and invaders who attacked Ipswich throughout its

history;

Christchurch/Holy Trinity Priory

timeline;

Historic Maps

page for a

note about the Ipswich claim to be the earliest continuously settled

town

in England.

Kings

and

Queens timelines (which includes architectural styles).

Home

Please email any comments and contributions by clicking here.

Search Ipswich

Historic Lettering

©2004 Copyright

throughout the Ipswich

Historic Lettering site: Borin Van Loon

No reproduction of text or images without express

written permission

1778 map

1778 map Turret Lane is named

after the Turret

(Garden) House which was demolished in 1843. It is a later name for

what must have been the

Dean's House to the north of the college site and which formed the main

entrance to Wolsey's College. The plan illustrated here, dated 1724,

shows the house at the top,

with turrets echoing those which are decribed as adorning the college

buildings. The positioning of this house and its gardens is indicated

on the sketch map of the whole college site as it was in 1528. The

red outline shape fits onto the upper part of Ogilby's

1674 map almost exactly

(down as far as Rose Lane).

Turret Lane is named

after the Turret

(Garden) House which was demolished in 1843. It is a later name for

what must have been the

Dean's House to the north of the college site and which formed the main

entrance to Wolsey's College. The plan illustrated here, dated 1724,

shows the house at the top,

with turrets echoing those which are decribed as adorning the college

buildings. The positioning of this house and its gardens is indicated

on the sketch map of the whole college site as it was in 1528. The

red outline shape fits onto the upper part of Ogilby's

1674 map almost exactly

(down as far as Rose Lane).

1674

map

1674

map

2020 image

2020 image

Wolsey's

College foundation stone

Wolsey's

College foundation stone  Facsimile in St Peter's

Facsimile in St Peter's

2014 images

2014 images 1960s

image courtesy The Ipswich Society Image Archive

1960s

image courtesy The Ipswich Society Image Archive

2021

image courtesy Syvia Patsalides

2021

image courtesy Syvia Patsalides