Courts

and yards in eastern Ipswich, 1880s

Charles Court, Wells Court, Shire Hall Yard, Lower Orwell

Street, Wingfield Street, Tankard Street

'5 January

2014. Just a "thank you" for the superb content on the

Ipswich lettering website. I have been researching my family history

for almost 50 years... they lived in St Clement/St Helen's parishes for

over 200 years, clearly in dire poverty. Your maps and insights add so

much colour and flesh to my image of their lives. Thanks, John

Welham'

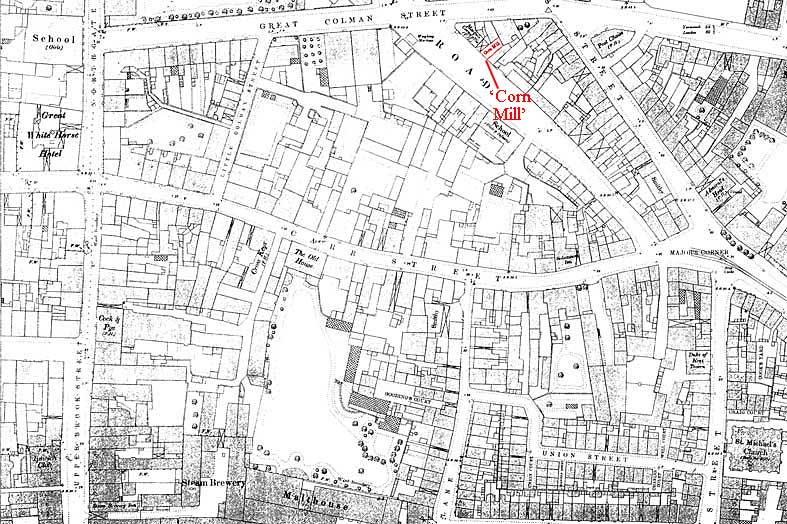

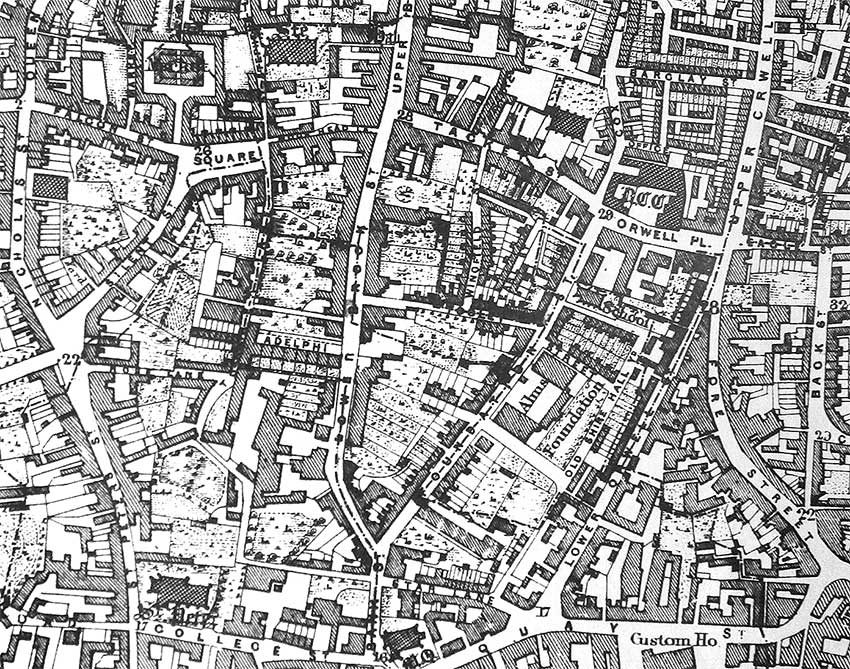

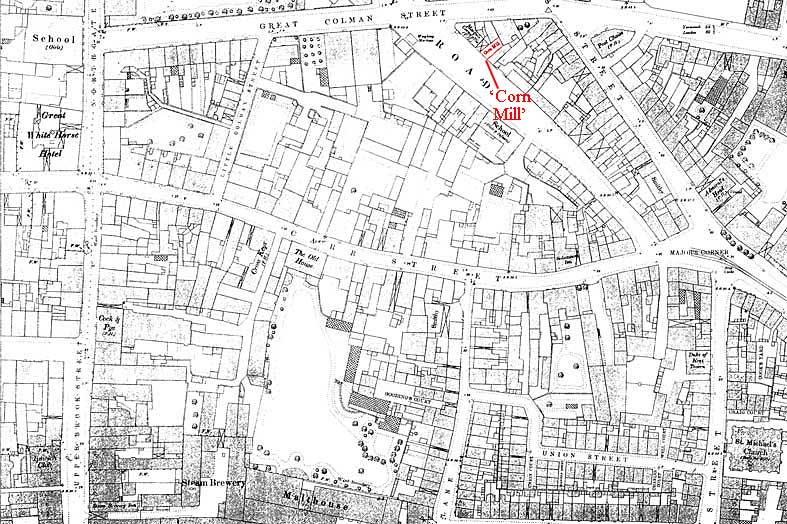

1881 map

1881 map

Carr Street area

We came

across this 1881 map detail which gives some

impression of the

density of lowly housing particularly in the east, bordering The

Potteries area. Cox Lane is at bottom-centre meeting Carr Street.

Running horizontally across the

centre is Carr Street from Majors Corner (where the tracks of the

horse tramway teminate – they weren't replaced by electric trams

until 1903) on the right to Upper Brook

Street

on the left.

See our page on The Potteries for a 1902

map from Cox Lane to Alexandra Park.

Notable features:-

1. Little Colman Street (upper

left) is there; the East Anglian Daily

Times printworks would be built in 1887 on the corner of Little Colman

Street and Carr Street and this was eventually demolished (1966) along

with the street, the Lyceum Theatre and all the neighbouring shops

before the

imposition of the disastrous 'Carr Precinct' – most of it

is now a cut-price store;

2. The building opposite the jaws of Great Colman Street is clearly

marked 'School (Girls)'; see

our Egerton's

page for more on this lettered building;

3. Upper Brook Street is very

narrow between the Symonds

Chemists corner and The Great White Horse;

4. Between Upper Brook Street and Cox Lane (centre, bottom of map) is

the

'Steam Brewery' and

'Malthouse'; these lie to the south of a large open

yard behind what was to become the Woolworth's store (marked 'The Old

House', which appears to have a large garden behind it reaching down to

the Malthouse); in 1856 Charles Cullingham and Ashton Blogg (who had

previously had a small brewery in Foundation Street – probably where The Unicorn Brewery stands today) had set-up a

Steam Brewery here. From 1873 its proprietors were Charles Cullingham

and Frances Blogg; by 1885 Cullingham was sole proprietor. The company

was a large concern, owning sixty-nine pubs and maltings. It was bought

by the Tollemache Brothers in1888 and it closed in 1958

when 'Tolly' merged with Cobbold, leading to eventual demolition to

become a car park;

5. Across Cox Lane is an indication of the extreme density of housing

in this poorest part of Ipswich at the time stretching eastwards: Union

Street,

Goodings Court, Union

Court, Daniela Court, Charles Court (see photographs below),

Well Court, Craig Court and Cook's Yard are visible; much of this area

(including the small Permit Office Street – so named because

an

inhabitant was an official who issued Custom & Excise permits)

was

demolished and became the Cox Lane car park; Watts

Court (scroll down)

further down Foundation Street still had a couple of

the

original small houses until 2013.

6. Apart from the still-standing Great White Horse, The Cock &

Pye

and The Salutation, we can see the following hostelries:-

- Steam

Brewery Tap/Inn: 39 Upper Brook Street, north of the archway;

see our Old Cattle Market page for

a closer look at these buildings;

- The Coach & Horses: 41

Upper Brook Street, south of the archway with its Winged wheels emblem);

- The Cross Keys Inn: a

coaching inn at 22 Carr Street which existed there before 1650 and

closed in 1938; the original building was extensively rebuilt when the

street was widened (c.1887-88) to allow trams to pass, now a charity

shop; see our Symonds page for more on The

Cross Keys;

- The Marquis of Cornwallis:

on the sharp corner of Old

Foundry Road and Great Colman Street, next door to a 'Corn Mill'

(marked in red above)

see our Vestiges

page);

- The Post Chaise: at the very

tip of St Margaret's Street and

Woodbridge Road with a loop lane behind it linking the two

roads; standing opposite The Mulberry Tree,

still standing today;

- The Admiral's Head: opposite

the jaws of

Carr

Street, on Major's Corner);

- The Duke of Kent Tavern: 10

Upper Orwell

Street

on the opposite side to

the St Michael Church, for many

years the former public houses was the offices of the Co-op funeral

service – see our Co-op page for a

photograph; a Urinal is marked

behind tenements on the

opposite corner to the church.

7. Note that the prominently-marked 'The

Old House' on the south side

of Carr Street was the home of James Allen Ransome (1806-1875),

director of Ransomes Sims and Jeffries. His extensive triangular garden

is to the south of the house. Ironically, perhaps, what must have been

a rather fine house fronting Carr Street is today a Poundland store

(formerly Woolworth's in one of the ugliest buildings in Ipswich); the

gardens are either built on or part of

today's car park. Such is progress.

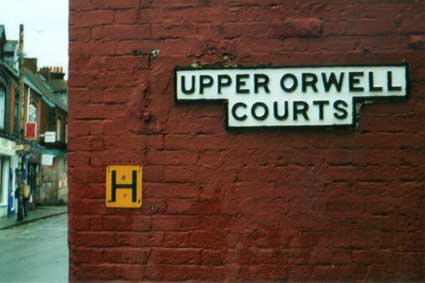

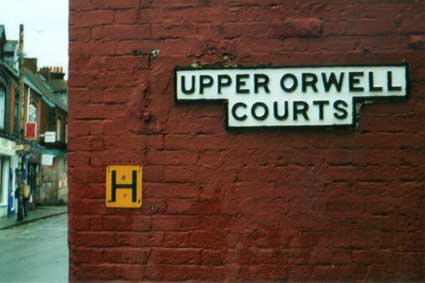

'Courts' and 'Yards' were small clusters of poor, overcrowded housing

often grouped around a small yard and accessed from the street by a

narrow passage. 'Upper

Orwell Courts'

still has its street sign, but is now just a narrow lane between Upper

Orwell Street and Bond Street. Muriel Clegg (see Reading

List) writes of houses (mainly one room up, one room down) with no

gas, electricity or

sanitation when an additional income could be had by storing human dung

from the inhabitants in a tank in the yard which was collected and sold

on to farmers to manure the fields. The stench and danger of disease

can only be imagined. In

the 1880s a network of sewers was dug in Ipswich (a notable feature of

those dug down the centre of Westgate Street was the discovery of a

series of medieval

burials. This work may well have been in progress at the time of the

above

1881 map. Through the 19th century private companies provided the water

supply but in 1892 the council took them over. See the Ragged Schools page for other signs of

extreme poverty in Ipswich when apparently its economy was booming...

Rags & bones

Rags & bones

A key source of information on this subject is Frank Grace's

excellent book Rags & bones

(see Reading List) which meticulously

documents the truly awful poverty of eight to nine thousand people

living in St Clement's parish in the 19th century. One or two examples

really bring the squalor to life. The area known for many decades as

'The Potteries' – roughly the site of

Suffolk New College, with the

'cliff' (scarp) up to Alexandra Park probably caused by clay-digging

was probably the source of raw material for the seventh and eighth

century wheel-thrown

pottery which was widely distributed in Britain and the Rhineland and

which is called by archaeologists

'Ipswich Ware' because of its characteristic composition and glaze. A

stratum of white clay was estimated by historian John Glyde in 1850 to

be thirty feet deep in this area

and there was, of course, plentiful local, fresh spring water. The

greatest number

of kilns was found just inside the late Saxon rampart and ditch which

ran down what is now Upper Orwell Street and 'St Helen's pottery

ground' succeeded these kilns in later centuries.The decline of this

ancient trade is the story told in Rags

& bones. In addition to

The Potteries, Rope Walk (literally a

rope manufactory) and the area

reaching round the bend in the dock from Neptune Quay and down the east

bank to Myrtle Street experienced a massive change from the 1820s. The

Rope Walk and Rope Lane were once cut off from the river by meadows

until Long Lane was cut through. The remnant of this today is the

southern stub of Long Street between the College and the University

running from the bottom of Back Hamlet into car parks. This lane was

eventually to form one of the worst slums in the town. The decline of

pottery, tile and brick-making as well as rope-making seems to have

triggered a burst of trading in plots of land, rapid building of

'cottages' with small pubs on the corners, grocery shops etc. (For a

1902 map of much of 'The Potteries' area, see our Potteries page; also the Holy Trinity Church page.)

All of this was driven by the profit-motive, not by philanthropy. Very

little or no attention was paid to decent infrastructure: paving,

drainage, access etc. Because it catered to the housing demands of the

lower and lowest strata of Ipswich society, the result was the building

of slums with appalling sanitation, overcrowding, disease and

exploitation of the inhabitants. The distance between the frontages of

the cottages varied from less than fifteen feet in David Street, even

less in Baker Street and nine feet in Short Lane. The last of these was

200 feet long and in 1881 there were eighteen households with 102

people

living there. It was similar in many ways to present-day shanty towns

which grow up on the edges of conurbations. Many of the people making

money from these ventures were

supposedly upstanding members of Ipswich society. People with power,

wealth and influence: politicians, mayors, businessmen resisted any

social reforms for decades, despite overwhelming evidence collected by

the Medical Officer of high mortality and degrading living conditions

over a large area of the town where 'repectable' persons might fear to

tread. The stench would certainly put them off. So much for the

enlightenment of the Victorian industrial

revolution and its resultant immense wealth and 'prosperity'.

'Cottage' is a word we like to associate with roses round the door and

a pleasant garden, perhaps a thatched roof. In the Potteries it was

more

commonly a 'single house', no more than a two-roomed shed with a blind

back, no doors or windows at the rear. In 1881, one such dwelling in

Clark's Court housed thirty-three people. The toilet would have to be

emptied by hand, through the house. Many cases of inadequate drains

becoming blocked are reported with the surrounding ground, paths and

buildings becoming contaminated with effluvia. Slums reported as being

health hazards, damp, overcrowded, disease-ridden, were no more than

twenty years old in some cases, so the landowners were not just

building the slums of tomorrow, but virtually the slums of today. There

are examples of builders being unable to finish their work because the

inhabitants were so desperate for housing that they moved into

unfinished premises. Needless to say, the builders gave up and left

houses unfinished. Some jerry-built houses on the clay layer of the

Potteries site, close

to the scarp either fell down or had to be demolished only ten years

after erection. In the 1880s a network of sewers was dug in Ipswich and

eventually the major contamination and public health problems of 'The

Rope Walk Insanitary Area', as it had come to be known, were

ameliorated. (Between 1879 and 1881 the sewer outlet was built

downriver from the dock.) In the 19th century private companies

provided the water

supply but in 1892 the council took them over. See our Street furniture

page for a note about Ipswich Water Works. Drainage, sewers, water

supply, paving, slum landlords: all unromantic subjects, but crucial to

the

chequered history of Ipswich and its people.

Another feature of the population of the Potteries area in the 19th

century detailed in Rags & bones

is its restless nature. People were coming into the area to seek for,

usually, very low-paid work then moving around to different addresses,

moving away and sometimes returning. Whatever societal structure

developed happened despite this perpetual motion. For the powerful

employers of the day, notably the dominant Ransome's, Sims and

Jefferies engineering works, this would be called "a flexible

workforce"...

An 1850 perspective

‘There are 106 courts in the town,

containing 627 houses. The drainage from some of these is very

defective. In some instances all the refuse water has to be carried to

a dead well, situated either in the middle or at the end of the yard.

In others, the water course is very badly paved, and stagnant water is

the consequence. The demoralizing practice of providing but one

convenience for several house is here seen in full force. No less than

67 courts, containing 358 houses, are in this position; giving an

average of one to every five houses. The courts are also equally

deficient in accommodation for the washing of clothes. Many of the

inhabitants have to perform that operation in their dwellings, to the

serious injury of their health and destruction of their comfort. The

supply of water to the courts is also of a defective character. Ten of

them are without any supply, to 4 the water they require is fetched

from the wells, and to 21 from pumps. The difficulty and labour

attending the procuration of this needful article, must have

deteriorating influence on the character of the inhabitants, and

prevent the formation of those habits of cleanliness so essential to

the health, comfort and moral elevation of the poorer classes. The

ventilation of the courts is bad, their situation often very confined,

and the entrance in some instances narrow. Some of their houses are

situated back to back. Above 500 of them have no back doors; and, in

the major portion, the rooms are so small that, where they are occupied

by families, they cannot fail of being crowded in the sleeping

apartments.’

Contemporary description of insanitary courts, John Glyde: Moral, social and religious condition of

Ipswich, 1850; quoted in Grace, F. The late Victorian town (see Reading list).

Frank Grace's The

late

Victorian town is a very interesting 'slim volume' designed by

the author as a teaching guide to research. Much of the book relates to

Ipswich and it is full of passages such as that above, also

insights into Franks' working methods and the way in which the stories

of people can be reconstructed from historical sources.

Charles Court, off Upper

Orwell Street

photos courtesy Dave

Riseborough

photos courtesy Dave

Riseborough

Above: 'CHAR[?]..S CT'

a street name painted on the brickwork of a wall at the

end

of the stub of Union Street (off Upper Orwell Street). Dave Riseborough

writes: 'On old maps I looked at on the internet it looks as though

there was a court there, but it is not named on the maps). It is

located up Union Street, off Upper Orwell Street. Towards the end, on

the left, there is an old building (I seem to remember reading

somewhere that this is an example of the old slum buildings that were

there and which was left after the slum clearances, but I can't be

sure) the sign is on the rear of this building...'

Certainly there is no name (not even Union Street)

on the map of Ipswich by Edmund White, 1867. The two streets crossing

at right-angles between Upper Orwell Street and Cox Lane are named

Barclay St and Office St. However, an Ordnance Survey (scale 1/1250)

map of 1883 given to us by Hilary Platts some years ago shows all the

names in this rabbit-warren of the poorest Victorian housing in the

centre of the town. This clearly shows, on the north side of Union

Street, Well Court and directly opposite: Charles Court. Thanks to Dave

Riseborough for bringing this hidden corner of historic lettering to

our attention. Below: location photograph of the vestigial Charles

Court lettering.

2014 image

2014 image

See Upper

Orwell

Court and Dove Yard for this and other metal street name

signs.

See Upper

Orwell

Court and Dove Yard for this and other metal street name

signs.

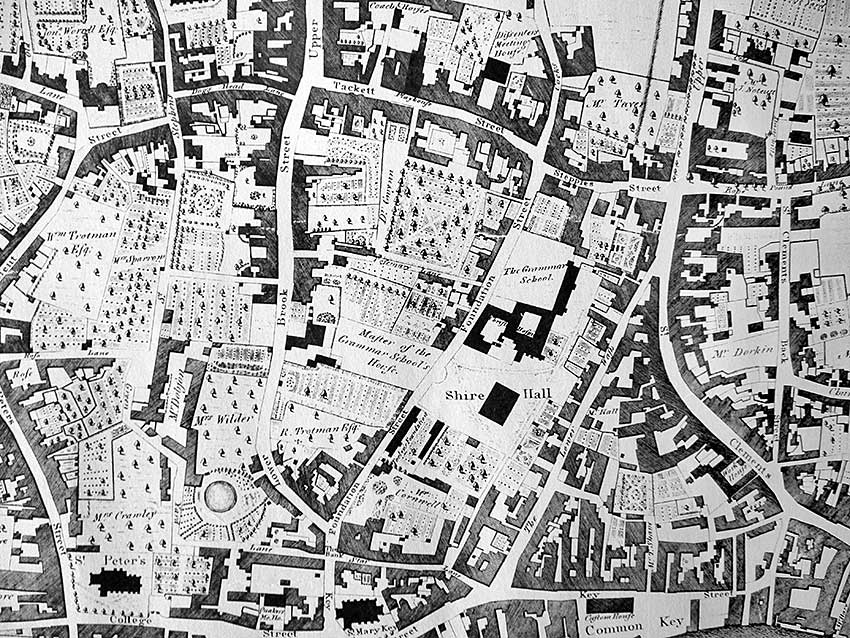

Shire Hall Yard area, off

Foundation Street

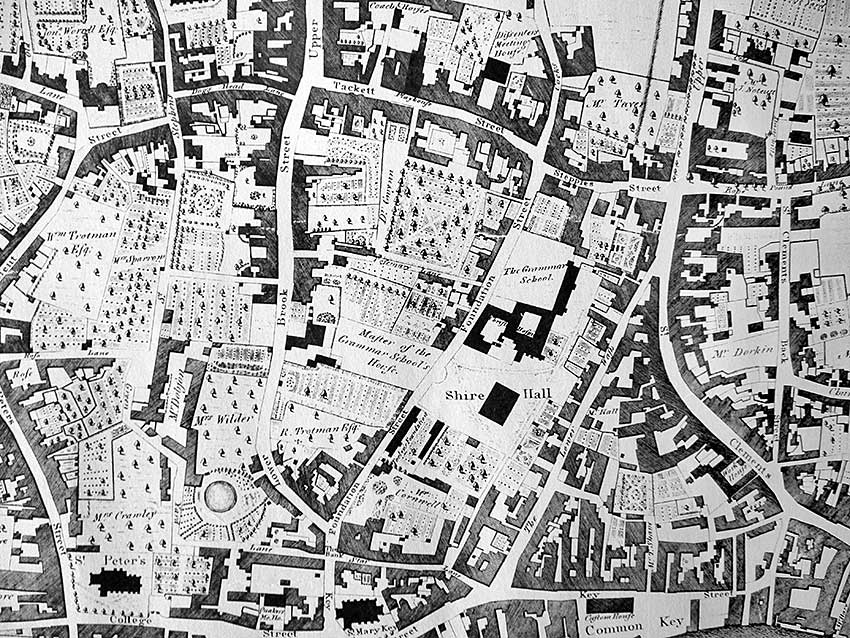

A comparison of Pennington's

map (1778) and White's map (1867), is

recommended by Muriel Clegg (below).

This detail of the 1778 map of the

area shows

the Shire Hall (built in 1699) at the centre with,

to the east of it,

today's Lower Orwell Street (labelled 'The

Lower Wash' here, running with spring water). 'Stepples Street'

(today's Orwell Place), named after the stepping stones which helped

people to cross the road without getting their feet wet, is at the

upper right. See our page on Water in Ipswich

for more on the springs and rivers.

The lane today called Pleasant Row runs from Shire Hall

southwards towards Star Lane and the dock. 'The Bank' (the 'Yellow

Bank', as distinct from Cobbold's Blue Bank– Whig and Conservative

respectively) is shown in Star Lane at

the southern end of Foundation Street; for a time it gave the name

'Bank Street'

to the small section of road down to 'St

Mary Key' Church. Here it is shown as a section of Key Street

curving round the church. This tiny road has also been treated as a

continuation of Foundation Street.

Today's Fore Street drops down from the Spread Eagle crossroads and

curves to the east but in 1778 it is labelled by Pennington 'St

Clements Fore Street'.

1778

map

1778

map

Watts Court doesn't exist in 1778; the site is an orchard across

Foundation Street from Shire Hall and beside 'The Master of the Grammar

School's House'. By the 1867 map Watts Court runs off the street to the

west between the 'D' and the 'A' of 'FOUNDATION' with a few dwellings.

The map of 1881further down this page actually labels 'Watts Court'

in this position (shown here in red), now fully built up with small

cottages on both sides. The Shire Hall has disappeared by this date,

1867map

1867map

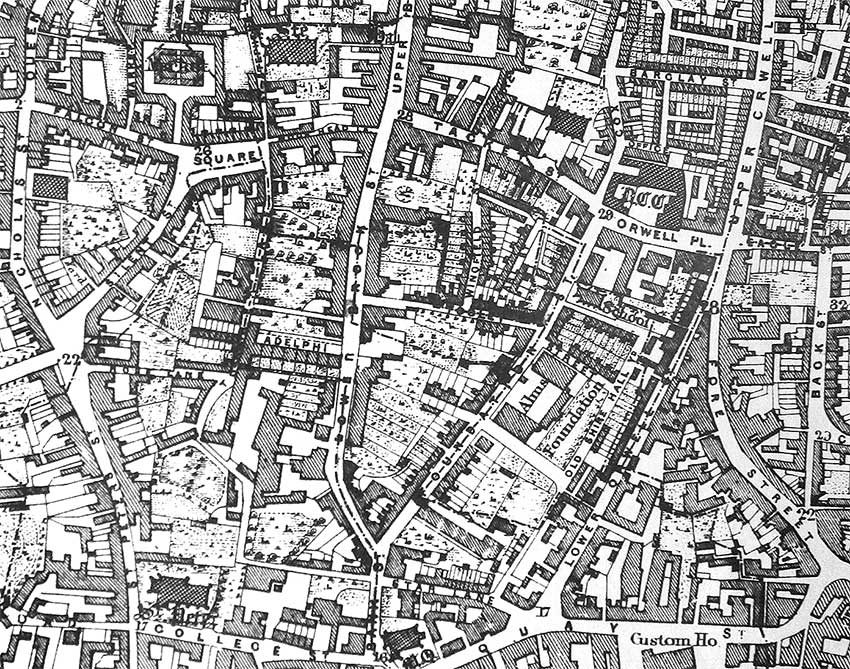

Below: this second map of 1881 is south of

that shown at the top of the page and labels the area 'Shire Hall Yard'

at

its centre lying between Foundation Street and Lower Brook Street. Tooley's and Smart's Almhouses (built by

J.M. Clark in 1846) lie underneath that caption. Many

features have changed or gone forever and the density of housing is

very striking. One survivor is the small house in Watts Court, still

standing until 2013 (see below). Watts Court

(shown here in red)

is off the west side of Foundation Street, level with the lower Shire

Hall Yard: this is now called Smart Street, where Smart Street School (marked as 'School -

Boys and Girls') can be seen, and that

page contains more information on 'Shire Hall' itself. Tooley Street (which is now called Blackfriars Court,

presumably renamed following

the rediscovery of the ruins of that monastic church nearby) completes

the northern part of Tooley's Almshouses

rectangle. Parallel

with and just north of that is the long-disappeared School Street, the

original site of Christ's

Hospital School with the Unicorn Brewery

above it.

1881 map

1881 map

Watts

Court, Foundation Street

[UPDATE 21.8.2012: "I stumbled

on this very interesting site. I know there were several courts

built for the poor in Ipswich, usually built behind houses on the main

streets. My mother was born in Craig Court off Upper Orwell St,

she grew up in Watts Court off Foundation St. In fact two of

these very small houses off Foundation St. still survive, they are now

used as some kind of storage facility. It would be great if you

could put a picture of the houses on your site before they disappear.

Also is are there any photos in the archives of these two courts.

Thank you for your time, Kind regards, Carolyn Saxon." In response to Carolyn's email, we have

added the maps of courts and

yards on this page and here are her 2013 images of those

houses. Thanks.]

2011 photographs courtesy Carolyn Saxon

2011 photographs courtesy Carolyn Saxon

[UPDATE: By spring 2013, this

humble building had been demolished (see below). "Unbelievable!

Doesn't anyone in Ipswich who has any say-so have the foresight

to save anything of historic value? I'm so glad I

took those pictures when I was home last (2011) & passed them on to

you. Just in the nick of time it seems. Thanks for letting me

know, Carolyn" (13.7.2013)]

2013 image

2013 image

Muriel Clegg:

‘Under the twin pressures of rapidly growing population and the demands

of industry, Ipswich, in common with there towns early in the

nineteenth century, embarked upon the dual policy of opening up the

town by the creation of new streets and infilling with rows of little

houses wherever space permitted. The departure of the better off to new

developments on the outskirts of the town left vacant the gardens and

orchards which for centuries had been a feature of the town. One has

only to compare the maps of Pennington (1778) and White (1867)*** to

see

the results. There is endless fascination in looking through nineteenth

and early twentieth century directories at the names of the little

courts, rows squares and cottages, often bearing the names of those who

built them. In the long history of the town it was a short-lived

development. The name-plate Watt’s

Court until recently hung as a solitary memento of that period,

when the town was crammed with people who actually lived in it. Watt’s

Court has been redeveloped but no-on lives there now. If nostalgia

threatens, a quick look at the 1874 report of the Medical Officer of

Health for Ipswich is an instant corrective. No-one can regret the slum

clearances begun ‘in earnest’ in the 1920s when many hurriedly built

and deplorably insanitary little dwellings were gradually swept away.

Yet during that phase of almost wholesale destruction when older

buildings shared the fate of newer, much was lost which a later

generation, bent on conservation, might have saved to grace an almost

denuded town. But the streets designed to open up the town and to

provide through ways are still with us.

'One of the earliest was Great Colman Street. The new road entailed the

purchase of ‘Harebottle’ House with one-and-a half acres of land,

offered for sale at the Great White Horse Hotel on 5th June, 1821. The

last occupant of the house was Mrs Elizabeth Edge, widow of the Revd.

John Edge, rector of Naughton and vicar of Rushmere. Unfortunately the

particulars of sale show only the new lay-out and do not describe the

house, which was to be demolished. Harbottle House (to give it its

original name) was a Tudor house built by John Harbottle, a successful

Ipswich cloth merchant who acquired property at the corner of Carr

Street and Northgate Street in 1538. Gradually he extended his

possessions in a north-easterly direction, building himself a house

described as ’lately built’ in 1539. The house was sold by his great

grandson, Sir Harbottle Grymston, in 1633. Little Colman Street was the

back driveway from the stables to Carr Street. Here was a Tudor house

which can be placed in context, but it is lost to us. A few years

ensued before the proposed new road was constructed. On August 21st,

1823, the Suffolk Pitt Club held its anniversary meeting in a temporary

building on the site. Clarke, whose History of Ipswich was published in

1830, wrote of it as only a proposed new road at the time. The new

street took its name from the Colman family, shown by Pennington as

having property there. Useful it may be, but the new street created a

confusing little pattern by cutting across the double encircling lines

of Old Foundry Road and St Margaret’s Street.’ Clegg, Muriel: Streets and street names in Ipswich

(see Reading list).

[*** See the comparison of these two maps of the Foundation Street area

shown above.]

"The usage of these street names is relatively modern. Muriel Clegg in

her booklet Streets and Street Names

in Ipswich [see

Reading List] describes the history of each.

Lower Orwell Street

follows the course of a natural stream the ‘Cauldwell

Brook’ that flows ‘from high ground to the east of the town

gave its name and its course to Spring Road. Swelled by more water from

Warwick Road (formerly Water Lane) the stream continued its course

along St Helens Street (Cauldwell – 'Cold well' – Lane) to Majors

Corner

where there appears to have been another stream. There it turned down

Upper and Lower Orwell Streets (the “Wash”) to reach the

river’. In 1959 ‘excavations in Shire

Hall Yard, behind

Lower Orwell Street, revealed that the rampart [of the town’s

walls] was constructed above a ditch (probably a boundary ditch of

between AD900 and AD1100. The stream bed provided earth and gravel for

the rampart, and itself, widened and deepened by these operations,

provided an outer ditch probably 18 to 20 feet wide’. The street

previously known as the ‘Wash’ or ‘Key Lane’

has never been a major thoroughfare. The ditch separated the area of

this site from the medieval town and in medieval documents property in

this area is described as in the suburbs of Ipswich. Fore Street

‘was originally St Clement’s Street’ or St

Clement’s Fore Street’. By the early eighteenth century the

name Fore Street had appeared, reflecting the approach to the

‘fore’ or foreshore, no longer apparent since the

construction of the Wet Dock opened in 1839...

Occupants of Lower

Orwell Street in 1881

It is possible to identify the essentially working

class nature of

Lower Orwell Street in the Victorian period from the list of occupants

and their trades as published in1881 Directory

of

Ipswich. The houses along this eastern side of the road were

listed in the reverse order beginning with: John Taylor the then

publican of the Gun Inn.

The other occupants of the street were:-

43 J.

Clarke, blacksmith,

41 Thomas Pettitt, chimney sweeper,

39 Peter

Lawson, tailor,

37 George Simey wheelwright,

35 Ebenezer Robinson, ship

builder and William Bennett mariner,

31 Peter Smith blacksmith and

wheelwright,

29 James Lord, hawker, and again Peter Smith and George

Simey,

27 Mrs Garrod, staymaker,

28 Joseph Church, shoemaker,

25 was

vacant,

23 George Andrews, french polisher,

21 Robert Powell,

brickmaker, and G & O Ridley, wine merchants,

19 & 17 John

Garrod coal dealer, (his premises adjoined Garrod’s Court),

15

Mrs L Southgate, machinist,

13 & 11 Thomas Harvey, baker,

9 Mrs

Collier charwoman,

7 Samuel Barrell, engine driver,

5 Mrs Cook, and

3

Walter Powell, labourer.

These were not the owners of the properties.

Behind the street frontage there were commercial premises sometimes

linked with the cottages or small houses along the street frontage. In

July 1892 a ‘Capital Freehold Malting Premises with stable,

coach-house & large yard also Five Freehold Cottages Tenements

forming one block with an area of about 45 perches, having long

frontages’ were offered for sale ... These were

situated in ‘Lower Orwell Street in the parish of St Mary Key,

Ipswich’. The malting was described as ‘Brick-And-Tiled

… with Three Floors, 80 Coomb Steep, Barley Chamber, Kiln,

Screening Room and Malt Store with Capital Well and Pump on the

premises, in the occupation of C. H. Cowell Esq’ and ‘New

Brick-And- Tiled Stable with large yard adjoining the Malting in the

occupation of Mr Gummersome also, adjoining, Five Freehold Cottage

Tenements & Wheelwrights’ shop, being numbered 21, 23, 25, 27

and 28 Lower Orwell Street’. The description continues ‘The

Whole forming a complete block with a Frontage to the Street of about

84 feet, and a Frontage to a Cartway on the south side of the premises

of 135 feet’. The premises were considered to be ‘well

worthy the attention of gentlemen engaged in Mercantile

pursuits’. The vendor was a Mrs Debora Barker."

(The above passage is an

edited version of an Appendix to a Suffolk County Council

archaeological assessment of Essex

Furniture Site, Lower Orwell Street, Ipswich, 2007.

http://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/catalogue/adsdata/arch-415-1/dissemination/pdf/suffolkc1-32281_1.pdf)

Wingfield Street (named after Wingfield's House)

A lane at its junction with Tacket Street; it elbows round to

meet Foundation Street, but its much smaller today than in the above

mid-1880s map (also shown on our Brook

Street page relating to Rosemary Lane). See Street name derivations. Our page on Tooley's & Smart's Almshouses shows a

1902 map of the area with Wingfield Street and Little Wingfield Street clearly shown.

See also our Christ

Church

URC/Baptist page for the Listing text relating to the

still-standing rear wing of Sir Anthony Wingfield's 16th century

mansion, next to the church, both of which stand back from today's

Tacket Street north pavement.

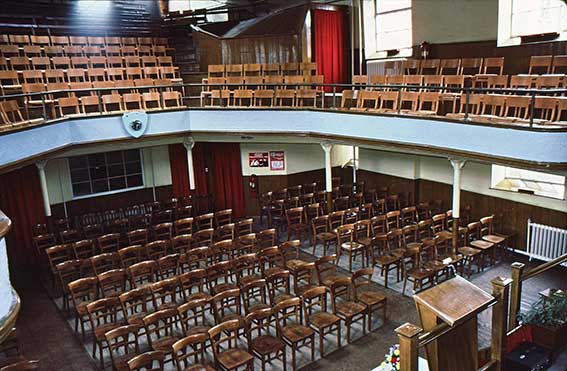

Tankard Street: the theatre and Salvation Army Citadel

Photo

courtesy Ipswich Society Image Archive

Photo

courtesy Ipswich Society Image Archive

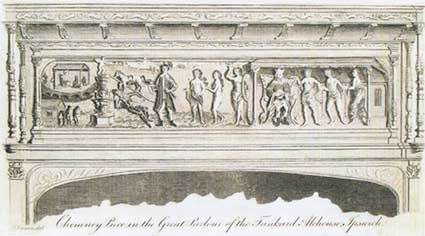

Above is a view of the north side of the narrow Tankard Street

(now Tacket Street – see Street name

derivations) looking east. The Tankard Inn had begun life as a

private house bought by Sir Humphrey Wingfield* from a Mrs Falstof –

probably after 1516 (the entrance to Wingfield Street is

opposite) which he decorated in palatial manner. Henry Davy's engraving

in Clarke's History and Description

of the Town of Ipswich (1830) [see Reading

list] shows that the magnificent panelled ground floor room with

even more elaborate ceiling decoration survived as a public room in the

Tankard Inn. It did so until Henry Ringham, woodcarver and church

furnisher (whose Gothic House is in St Johns Road, shown on our California page), was in 1856

instructed to strip the room of its panelling, repair it and use most

of it to line the walls of the study at John Cobbold's residence, Holy

Wells. In 1929 the oak overmantel and wall panelling, some of it

heraldic, was moved again to find a permanent home in the Wingfield

Room at Christchurch Mansion.

[*Sir Humphrey Wingfield

(c.1481-1545) was an English lawyer and Speaker of the House of Commons

of England between 1533 and 1536. For more on his fascinating life and

relationships to Charles Brandon (c.1484-1545), Duke of Suffolk who

married Mary Tudor (1496-1533); also to Cardinal Wolsey and to Ipswich

and its county – see The

Wingfield Society website.]

See also our Withypolls memorials

page for Sir Humphrey's role (along with his neighbour, Sir Thomas Rush) in the sale of the

Holy Trinity Priory site and the early days of Christchurch Mansion.

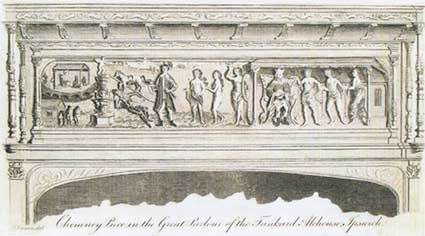

Above: the illustration of the 'overmantel' from the Great Parlour in

the Tankard Inn, from Blatchly, J.: Isaac

Johnson, see Reading list.

From 1738 of the eastern part of the Wingfield's

House was used for the Tankard Inn and the

western part of the site for a Playhouse. The Salvation Army Citadel in

the foreground of the above image began life on the

site of the

first permanent theatre in Ipswich; it was built by Henry Betts, a

local brewer and owner of the Tankard Inn in 1736. In 1741 it is

claimed that an unknown

actor called Lyddal made his debut appearance as an African slave

called Aboan in Thomas Southerne's play Oroonoko. This unknown actor was in

fact the soon-to-be-famous Shakespearian, David Garrick. The original

theatre was replaced by the Theatre Royal in 1803. It closed as a

theatre in 1890 and became a Salvation Army barracks. All of the

buildings in this view were demolished during the widening of Tacket

Street (the Citadel relocated to Woodbridge Road in 1994). Today’s

entrance to the NCP car

park covering the site of the

old Steam Brewery is at the immediate left of this picture. Even after

conversion into a Salvation Army Citadel, it is said that parts of the

'auditorium' comprised some original theatrical fittings.

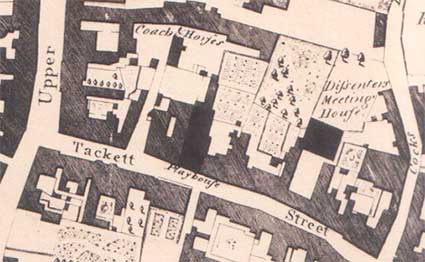

1778 map

1778 map

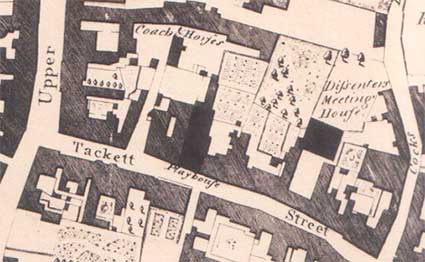

Above: a detail from Pennington's map of

Ipswich, 1778 showing the 'Playhouse' clearly labelled in 'Tackett

Street'.

Tankard

Innc.1830

Tankard

Innc.1830

Above: The Old Tankard in around 1830, converted from part of Sir

Anthony Wingfield's house, the inn took the name from Tankard Street,

formerly and now: Tacket(t) Street.

For much more on Wingfield's palatial house see A

house fit for a Queen:Wingfield House in Tacket Street, Ipswich and its

heraldic room by D.

MacCulloch and J. Blatchly. Suffolk Institute, 1993.

The website Theatres and

Halls in Ipswich, Suffolk (see Links) has an engraving

of the original, early 18th century theatre in Tankard Street and a

more detailed history.

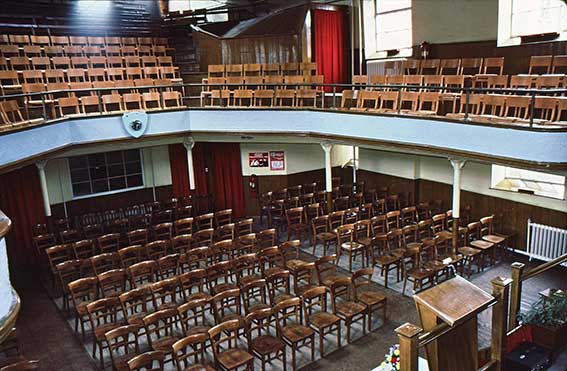

Above: photographs of the interior of the Tacket

Street Salvation Army Citadel, courtesy Morvyn Finch, to whom our

thanks. The galleried hall with its cast iron pillars bears striking

resemblances to others in the town, e.g. the nearby Christ Church URC and Museum

Street Methodist Church.

See our Christ's

Hospital School page for its move from Foundation Street/School

Street to Over Stoke.

See also our Historic

maps page.

Home

Please email any comments

and contributions by clicking here.

Search Ipswich

Historic Lettering

©2004 Copyright

throughout the Ipswich

Historic Lettering site: Borin Van Loon

No reproduction of text or images without

express

written permission

Rags & bones

Rags & bones 1881 map

1881 map Rags & bones

Rags & bones photos courtesy Dave

Riseborough

photos courtesy Dave

Riseborough 2014 image

2014 image See Upper

Orwell

Court and Dove Yard for this and other metal street name

signs.

See Upper

Orwell

Court and Dove Yard for this and other metal street name

signs.

1778

map

1778

map 1867map

1867map 1881 map

1881 map

2011 photographs courtesy Carolyn Saxon

2011 photographs courtesy Carolyn Saxon 2013 image

2013 image

Photo

courtesy Ipswich Society Image Archive

Photo

courtesy Ipswich Society Image Archive

1778 map

1778 map Tankard

Innc.1830

Tankard

Innc.1830